Inside El Salvador’s Mega-Prison: A Fortress of Brutality in the Name of Security

San Salvador – July 2025

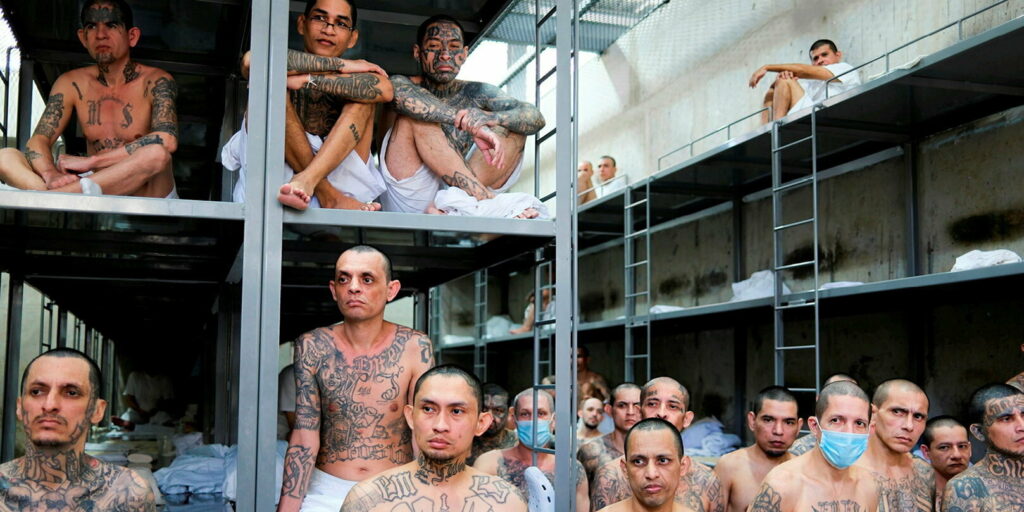

In the heart of El Salvador, a chilling monument to President Nayib Bukele’s war on gangs has taken shape. The Terrorism Confinement Center (CECOT), built to house up to 40,000 alleged gang members, has drawn global attention—not for its scale, but for its extreme conditions and what human rights groups call a “system of mass repression.”

Mass Arrests Without Due Process

Since the declaration of a nationwide state of emergency in March 2022, more than 63,000 individuals have been arrested, most without warrants or legal representation.

Miguel Montenegro, director of the Salvadoran Human Rights Commission, warns that CECOT is already overcrowded. “This facility will undoubtedly exceed its stated capacity, becoming a symbol of shame for the nation,” he told reporters.

Steel, Surveillance, and Suppression

Located in Tecoluca, 74 km southeast of the capital, the prison complex spans 166 hectares and includes eight massive concrete blocks. Each block has 32 cells, each around 100 square meters, designed to confine more than 100 inmates per cell.

Despite the numbers, cells are equipped with only 80 steel bunks—with no mattresses—and just two sinks and two toilets. Prisoners will be under 24/7 video surveillance, with barred doors allowing constant monitoring.

No Sun, No Air, No Freedom

Inmates will never leave their cells unless taken to virtual court hearings or placed in solitary confinement—dark, windowless rooms used for punishment.

There are cafeterias, recreation rooms, gyms, and ping-pong tables—but these are strictly for prison guards, not inmates.

Technology Meets Oppression

The entire complex is monitored by hundreds of cameras, with body scanners and full inspections for anyone entering. Over 850 armed personnel—600 military and 250 police—secure the perimeter, aided by signal jammers to prevent mobile communications.

Inside, guards patrol armed with handguns and assault rifles.

“Revenge, Not Justice”

Deputy Minister of Justice and Public Security, Osiris Luna, stated that all “terrorists responsible for the suffering of the Salvadoran people” will serve their sentences under the harshest regime. Inmates will be forced to work as a form of restitution.

But not everyone agrees with this approach. Jesuit priest and university rector Andreu Oliva argues for rehabilitation over revenge. “Prisons should aim to change people. They deserve a second chance,” he said.

Critics Sound the Alarm

Human Rights Watch recently reported extreme overcrowding in El Salvador’s prison system, which was already operating well beyond its 30,000-inmate capacity—before the opening of CECOT.

President Bukele hails the prison as a “monumental step” in his war on gangs, launched after 87 people were killed over a single weekend in March 2022. He claims past governments were too lenient, allowing gang leaders access to prostitutes, PlayStations, phones, and even laptops while incarcerated.

Now, CECOT stands as a fortress of discipline, with 11-meter-high walls, electric fences, and seven watchtowers, all constructed in just seven months by 3,000 workers. The government has not disclosed the total cost of the project, nor when the first prisoners will be transferred.

Is this the future of criminal justice in Latin America—or a warning sign of authoritarianism disguised as order?

Would you like a shorter version for social media, or translation into Arabic or French?